«Given that her complete catalogue is composed almost entirely of work she produced as a student, the posthumous critical esteem for American photographer Francesca Woodman is astonishing. Unlike music or math, where precocious displays of talent are not uncommon, photography tends not to have prodigies. Woodman, who committed suicide in 1981 at age 22, is considered a rare exception. That she has achieved such status is all the more remarkable considering only a quarter of the approximately 800 images she produced—many of them self-portraits—have ever been seen by the public.

Now, on the thirtieth anniversary of her death, Woodman is having something of a moment. In coming months, her work will be shown by several British galleries, and later this year San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art will mount a major retrospective of her work, the first of its kind in the United States. In 2012, the show will travel to the Guggenheim. The Woodmans—C. Scott Willis’s thoughtful new documentary about the photographer and her family—opened last week at Film Forum in New York.

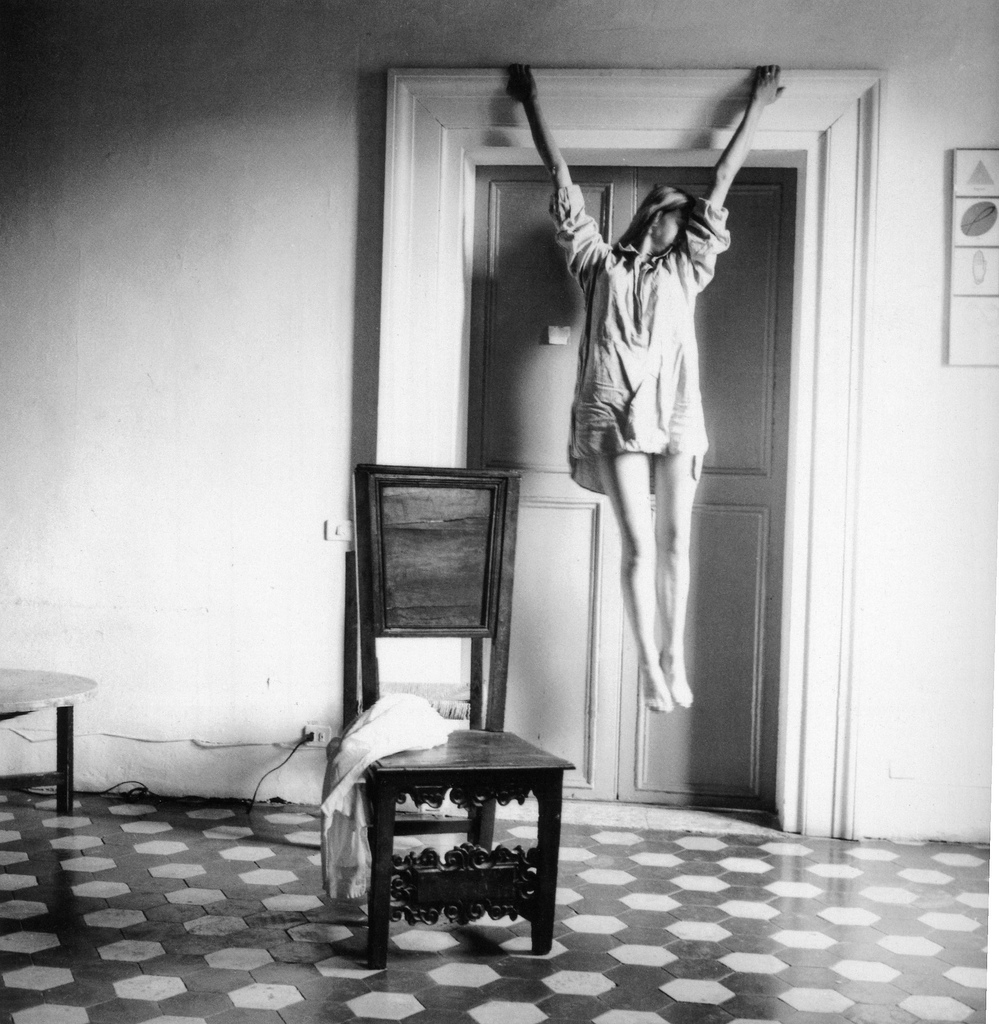

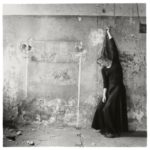

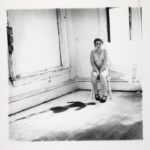

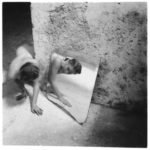

Taken between 1972 and 1981, Woodman’s photographs are almost all black-and-white and have a general softness of focus not often seen these days. They depict a world almost identical to the one captured by earlier generations of photographers, as if Woodman’s camera were a filter through which the neon clutter of contemporary life could not pass. Some of these images have the polished smoothness of Surrealist photographs, like those of Man Ray and Hans Bellmer, in which precisely-rendered objects are arranged so deliberately it seems the slightest movement would alter the meaning entirely. (Fluent in Italian, Woodman spent her junior year in Rome, where she paid frequent visits to the Libreria Maldoror, a bookshop-gallery that specialized in work about and by Surrealists, and which ultimately hosted her first small show.) She makes use of many Surrealist motifs, among them mirrors, gloves, birds, and bowls. Like Magritte, she often shrouds her subjects in white sheets.

Her concealed figures, however, call to mind corpses, or ghosts, as if the wall between our world and the spirit realm had begun to fall. In her images, dust abounds, and there are no new buildings, only ruins, whose disintegrating forms evoke the wrecks admired by the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Gothic revivalists often cited as major influences. The out-of-focus figures are faint and friable-seeming, and Woodman’s gray tones as powdery as crumbling stone. “To Die,” reads the inscription on a Victorian tombstone that appears in one of Woodman’s early images, “is Gain.”

The phrase is more than apt. What little is known of Woodman’s archive has proven itself capable of supporting a monumental reputation, the nude portraits of herself and other young models bearing much of the weight. Since her rediscovery in the mid-1980s, Woodman has continued to attract the attention of audiences and critics. Her work is in the permanent collections of many museums—among them the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art—and her style has so informed other professional and amateur photographers that effects she pioneered now appear in catalogues and ad campaigns and fashion spreads. She can even be credited with the coining of visual clichés: shots of women’s legs, a Woodman favorite, are now considered the adolescent’s stock in trade.»

Comments are closed.